THE GAUSSIAN SPECTRUM OF LIVING

THE GAUSSIAN SPECTRUM OF LIVING

An Axiological Thought Experiment

Transport yourself back to a Classical Athenian Symposium during the 4th Century BC and envision three fervent philosophers (A,B and C) converging to unravel the profound inquiries that shaped the essence of Ancient Hellenic society. These youthful intellectuals radiate a contagious intellectual vigour; their discussions flow seamlessly among the symposium’s participants, seemingly immune to the intoxicating effects of the wines swirling in their bronze goblets. Amidst the flickering torchlight and the scent of aromatic oils, their debates intensify, unravelling old answers while birthing fresh questions. With each exchange, they engage in a relentless pursuit of truth, challenging and refining each other’s arguments in a perpetual cycle of emergence and decay.

It is in these moments of rigorous inquiry, during symposia of classical Athens, that the true essence of philosophy reveals itself in its classical setting—a perpetual quest for an understanding that thrives on the tension between emergence and decay, continually reshaping its contours with each dialectical turn. The young philosophers, as guided by teachings of their masters, engage in a relentless pursuit of wisdom, refining and refuting each other’s arguments. However, though initially undeterred by the psychedelic properties of their beverages, after an hour of insightful debate the symposium reshapes its humble ambience descending into a hedonistic anarchy as each philosopher strips apart their chiton and explore the abyss of their bodily desires on each other culminating in a deep slumber that lasts till dawn when the philosophers are awaken and leave the scene without a single lexicon.

This analogy forms the foundation of the Gaussian Spectrum of Living, a simplistic philosophical model derived by 18-year-old Eurytus as he obsequiously observed the proceedings of that night, being awake throughout the symposium while not taking sip of the wine he was refused from drinking. Amongst the many axiological questions that emerged that night as the trio discussed and debated, Eurytus was most intrigued and drawn to the most basic yet complex question of them all “How to live one’s life?”. Through his eye-witness, he labels each philosopher with an ideological response to the question and draws what he believes is a diagram that applies the question and explicates it to the Hellenistic population he knew and lived amongst. The following is a summary of his record:

The Trilogy of Thought

At the start of the symposium, the three philosophers began with casual conversations about personal and political matters. As the night progressed, their discussions evolved into intense philosophical debates, sparking a continuous cycle of questioning and answering. Their shared goal seemed to be reshaping the Hellenistic world through logic and reason. Yet, this intellectual pursuit was short-lived. As they indulged in wine, their focus shifted, and the symposium transformed into a scene of extravagant sexual indulgence. Despite each philosopher encapsulating a different response to the question on how to live one’s life, the trio had unconsciously lived through each of their responses as they cycled through that night, To live as a realist, To live as an idealist or To live as a hedonist. Despite their paradoxical behaviour, each had his own intuitions, so one was a realist and the other was an idealist while the other one was a hedonist. Here they are described:

- Philosopher A – The Idealist who slurped on a syrupy fluid of Mastika, He leads a school of thinkers that claims a minority equivalent to the holding of C. His embodiment of human life is a machine of change capable of unleashing his potential for either himself or the world by recognising and reconciling the power of his mind and intellect to actualise wonders that cure his soul and the souls of others. Through gradually climbing the ladder of life and by ameliorating our psyche, our body and soul we are pushed further to supreme heights of humanity whereby we realise our full potential and change the ways of the world, only for the greater good. We may die with a goblet of hemlock, an arrow pierced into our skin or a natural death on a tranquil bed but we know we have full filed our role as humans and not as animals.

- Philosopher B – The Realist who slurped on a plain goblet of wine, He leads a school of thinkers that claims more students than those of A and C. His embodiment of human life is cycle of debts that gradually troughs and peak as we progress through stages. These debts are commitments, obligations and duties that one must satisfy and complete in his lifestyle without overdoing or underdoing. Through gradually flattening what he refers to as our ‘debt curve’ and through conforming to the norms, constructs and expectations of the social fabric we humans are freed from the complexities of existence and our obligations to society and become part of the population that dies a peaceful death in a tranquil bed.

- Philosopher C –The Hedonist who relished the aged wine, leads a school rivaling A and B combined. He views human life as an unrestrained celebration of pleasure, rejecting societal norms and moral constructs. For him, true fulfillment comes from indulging in all forms of gratification—be it sensory or sensual. According to Philosopher C, the essence of human existence lies in maximizing personal enjoyment without the constraints of societal expectations. He advocates a life free from moral obligations, where happiness is found in the immediate pursuit of pleasure. By embracing desires and passions unapologetically, he believes individuals can achieve the highest state of happiness and fulfilment.

The Schools of Living: The Gaussian Spectrum

Despite the tumultuous events of that night, the three philosophers articulated their distinct arguments in a manner that profoundly addressed the question of “How should one live one’s human life?” Yet, what reveals a paradox within their thinking is how each philosopher embodies aspects of the others’ schools of thought through their behaviours on that night. Initially resembling B, the realist, they discussed practical obligations and societal norms. As the symposium progressed, their discourse elevated to resemble A, the idealist, emphasizing change and human potential. However, as the influence of alcohol grew, they eventually descended into the hedonistic perspective of C, indulging in sensual pleasures.

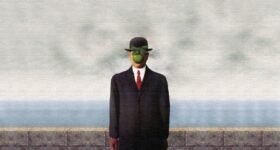

This progression mirrors the complexities of the Hellenistic world, where individuals grappled with varying approaches to life. The realist perspective, akin to Philosopher B, resonated with those who sought stability through fulfilling social obligations and duties. The idealist viewpoint, akin to Philosopher A, appealed to those driven by aspirations of personal and societal transformation. Conversely, the hedonistic outlook of Philosopher C catered to those who prioritised immediate personal gratification over societal norms and moral constraints. Eurytus used the infamous, Normal Distribution curve, as we now know it, to embed the Hellenistic population into these schools of though as denoted by the philosophical trio. They yield a fascinating insight that maybe akin to how the current world’s population fits into these schools of thoughts as described below:

- A (10%) – Amongst us humans, there exists only a minority that goes onto questioning and challenge societal systems, hierarchies and constructs with an intrinsic aspiration to better mankind through whichever endeavour it maybe. They may comprise a mere 10% of the population and are bold risk takers who maybe targeted for the ideas or values they introduce. These people reciprocate the ideology of Philosopher A (The Idealist). Eg: Socrates

- B (80%) The majority of us fit into B who live by the flow by conforming to social norms, constructs and hierarchies and do not intend to go further in advocating change or progressing mankind. They may comprise 80% of the population and are ambivalent beings. These people reciprocate the ideology of Philosopher B (The Realist). Eg: Athenian Free Women

- C (10%) – Finally, there exists another minority that goes onto challenge societal systems, hierarchies and constructs with a more self-interested aspiration which maybe to pursue pleasure in either way, be it good or bad. They may comprise another mere 10% of the population and are often characterised as non-altruistic and selfish for having echoes pleasure as their highest virtue. These people reciprocate the ideology of Philosopher B (The Hedonist). Eg: Aristippus

Leave a Comment