Severed Heads, Love Triangles & The Last Supper?: Reinterpreting the Controversies of The Paris 2024 Opening Ceremony An Year Later

Severed Heads, Love Triangles & The Last Supper?: Reinterpreting the Controversies of The Paris 2024 Opening Ceremony An Year Later

On the night of July 26th, 2024, Paris reunited the world in the spirit of sport by inaugurating the Games of the 33rd Olympiad after four tumultuous years marked by war, geopolitical turmoil and economic calamity which continues to persist. The evening featured a ground-breaking ceremony set along the River Seine, where thousands of athletes sailed past artistic performances and Parisian architectural wonders along a 6-km stretch, culminating at the iconic Eiffel Tower where the ceremonial formalities commenced and the games were declared open. The ceremony featured 6,800 athletes from 205 delegations on 85 boats. Despite the prevailing anxiety surrounding the safety of the event, exacerbated by earlier arson attacks on the French rail network, the ceremony was a resounding success, showcasing a vibrant display of French history, art, and culture, highlighted by surprise performances from Lady Gaga and Celine Dion.

The Worst Opening Ever?

Amidst the echoes of awe and wonder that resonated amongst athletes and spectators following the ceremony, many netizens were profoundly disheartened and deeply offended by several of the ceremony’s key performances. These included what appeared to be a re-enactment of Da Vinci’s Last Supper using drag artists, severed Marie-Antoinette heads on the Conciergerie followed by a suggestive love triangle. Outraged individuals took their rage to the comment sections of social media, which quickly waged into a full-on conflict as keyboard warriors in iterative rounds labelled the ceremony as ‘satanic’, ‘a disgrace to western civilisation’ and a ‘gay pride parade’ amongst many other derogatory phrases. The uproar was primarily echoed through socially conservative and right-wing leaning figures including social media influencer Andrew Tate, SpaceX-owner Elon Musk and former president Donald Trump. Against this outcry of negativity, however, French president Emanual Macron, thanked the artists, directors, performers and producers who were behind the ceremony and its superlative organisation having transformed a city into a stage and adapted well to the heavy rain that threatened to disintegrate the ceremony.

Although I empathetically understand the rage of those offended by the ceremony and their underlying reasons, I believe these reasons are based on flawed evidence and an ethnocentric understanding of French culture and history that has limited them to a very shallow and limited view of the ceremony’s key themes and ideals. Moreover, much of the uproar seemed politically oriented, creating ideological splits and battlegrounds between liberals and conservatives, of which the latter found the ceremony to be a display of ‘wokeism’. For me, these battlegrounds seemed like mere extension to the familiar US culture war and were propagandized in that they illustrated the deep-seated political polarisation of US citizens and its propagation to the rest of the world. In this way the ceremony’s controversies were illustrative of our failure as a society to think critically beyond a visible narrative and extract the inherent substance behind an artistic performance and its underpinnings. They represent our deep-seated attachment to moral circuits and politically-correct spectrums, instilled through institutions like media, politics and religion, that have consequently curtailed our capacity to think beyond the box and our own culture. Hence, it my humble exercise, in this article to decipher the inherent symbolisms of the most memorable and key performances of the Paris 2024 Olympic Ceremony that would hopefully help progress viewers from shallow labels like ‘satanic gay parade’ to more critically-thought and culturally-relativistic perspectives that underscore the core essence of the night’s performances.

The USP of Paris 2024: Liberation from Stadiums

France’s commitment to break free from the constraints, norms and constructs that hinder mankind’s capacity to manifest its creativity was instantly evident through its clever choice to not house the ceremony in a traditional stadium. By choosing to move out from the often limited, restricted and circular space of a stadium and extending the ceremony across the city enhanced the creation of a rich visual tapestry that propagated the Olympic Spirit throughout both Paris and the world. Being a record-first in Olympic History, we witnessed a unique parade of nations as Athletes passed the Parisian bridges, museums and gardens on boats that highlighted their presence and their centricity to the Olympic games thereby fostering their sense of belonging to the city that they would call home for the next 16 days. Unlike traditional stadiums, where athletes parade in a hierarchical formation, this method enhanced their visibility as a united team whilst providing ample opportunities to socialise with subsequent teams on boats thus fostering the inherent communal aspect of sport.

As the boats travelled across the Seine till it reached its terminus at the Eiffel Tower, Athletes and audiences witnessed numerous artistic displays, performances and narratives that punctuated the culture, character and values of Paris against a backdrop of prominent buildings ranging from the Notre Dame, Louvre & Orsay museums and the Conciergerie. By embedding the city with the ceremony, we can finally recognise that an Olympic ceremony does not have to be limited to a restricted space and is an event that must celebrate the culture of an entire city. Moreover, the act of not using a stadium and extending the ceremony through Paris, maybe in itself a gesture of France’s long-standing value for freedom celebrating how the liberation from pre-ordained constructs can ignite the beauty of all universal creative endeavours. This execution must also be appreciated for its managerial and technical complexities against the added pressure of an endless rainfall, France showcases its relentless ambition and skills in its ability to coordinate such a ceremony from safety needs to timing to its synchronisation with television screens underscoring the hard work needed to pull off such a spectacle. Our gratitude must be directed to the timeless artists, performers, stunts actors, directors and media personnel who covered this ceremony despite its complexity.

I am confident to say that this ambitious feat of a non-stadium ceremony is the USP of yesterday’s spectacle and has set the bar high for future opening ceremonies which would have to think beyond the box or beyond the stadium in order to truly create a ceremony that would stand against the sheer magnificence, scale and dedication behind the Paris 2024 opening (Side Eye: LA 2028). Beyond the non-stadium concept, in the next few paragraphs I aim to deconstruct the most provocative segments of their ceremony and try to rationalise with their purpose and meaning while also mentioning a few of the memorable and spectacular events of yesterday’s opening.

The X-Torch Bearer, Children & The Catacombs

Embedded into the ceremony was a rather peculiar narrative involving a mysterious torch bearer dressed in imperial attire traversing the city and streets of Paris performing stunt acts on rooftops, buildings and the river often leading to the reconciliation of content with performance thus progressing the ceremony and its overall story. The narrative commenced as French football player, Zinedine Zidane was deterred from carrying the Olympic torch due to a train delay and instead hands it over to 3 children who upon exploring the horrors of the catacombs meet the mysterious man who invites them onto his boat which takes them to Seine where the parade of nations commenced. As a first-time viewer, the entire narrative seemed odd and off, but upon further rounds of reasoning I believe I have coined together a compelling explanation that synthesises the story with the ceremony.

The main symbols in this complex opening narrative are the river, catacombs, children and the x-torch bearer. The Seine River, flowing continuously, symbolises the ever-present flow of life and time, carrying with it the essence of past civilisations and nourishing the current one. It is the thread that connects all generations, emphasising the pivotal role of rivers and water in shaping human history and being the source of all earthly life forms. Meanwhile the catacombs serve as a sombre yet profound reminder of mortality and the legacy of those who came before us who would have played a foundational role in the development of cities like Paris. Within this underworld, the X-torch bearer in his imperial attire appears to be a prominent figure from this macabre world, particularly reminiscent of Napoleon Bonaparte, a forefather of Modern-day France. As a symbol, he stands for ambition, progress, and the shaping of a nation’s identity providing a link between historical influence and contemporary aspirations. Lastly, the children represent the future, filled with hope, potential, and the promise of new beginnings.

Their journey through the catacombs, guided by the Napolean amidst lost generations, signifies a rite of passage illustrating the passing of knowledge, wisdom and blessings from one generation to the next where the young absorb the lessons of the past to build a brighter future for the next generation. The children, carrying the torch of previous generations, emerge from the depths of the catacombs into the light of the river, ready to embark on their journey. In this intricate interplay of symbols, the narrative emphasizes the importance of remembering and honouring our past while courageously forging ahead. It is a story of unity, resilience, and the perpetual quest for progress, where each generation builds upon the foundations laid by those before, moving ever forward in the great river of time. This passage through history, guided by the legacy of leaders like Napoleon, empowers them to shape their destiny and contribute to the ongoing story of civilization.

In no way do I deem my interpretation to be absolute. Olympic Opening ceremonies, like yesterday’s, provide rich visual performances and narratives that embed viewers into them by seeking their critique and interpretation. We have a choice here, we can either interpret it negatively and propagate hate or we can interpret reasonably and seek reconciliation between culture, sport and artistic expression. I seek the latter route and by connecting the symbols of this story I have come to realise that it was more than just an amusing narrative but a true reminder of acknowledging the past as we work towards the future in the spirit of progress. This has been presented to us in an entertaining and peculiar way that I reckon only few would wish to venture deep and see the complex interplay between symbols and humanistic messages.

Gojira, Satanism & The French Revolution

The entire Olympics opening ceremony followed a predictable structure. Having established the connecting narrative at the start, it featured the parade of nations that was frequently interjected with performances and videos depicting French culture, art and history that was played atop bridges and river banks as athletes passed by. These performances would at times be intertwined with the X-torch bearer’s narrative, sometimes in real-time, providing an almost exuberant and animatic presence throughout the ceremony. One interjection, as vaticinated, was a reference to the French Revolution and its purpose in setting forth freedom, equality and brotherhood. It commenced with a quick theatrical performance at The Chatelet from Les Misérables involving the angered masses singing ‘Do you hear the people sing?’ which was quickly followed by a humorous depiction of a beheaded Marie-Antoniette at a window of the Conciergerie, infamously the site of several beheadings during the 1700s. The mere act of embedding the French revolution was crucial underscoring France’s relentless ambition to achieve freedom and sovereignty and the performance that followed was no less different to this message.

It is here that we meet French band, Gojira, singing “Ça ira,” a song symbolic of the French Revolution, in a hard-rock style, while choir members dressed as Marie-Antoinette adorned the windows of the Conciergerie as an opera singer on a boat sailed alongside the building. This formidable scene, complete with whisps of fire, red confetti and fireworks, powerfully epitomises a rich visual tapestry that proudly depicts the tumultuous and transformative period of the French Revolution.

The hard-rock rendition of “Ça ira” boldly resonates the rebellion and flaring fury of the revolutionaries, while the Marie-Antoinette costumes in the windows evoke the stark contrast between the monarchy and the plight of the common man. The spouts of fire and red fireworks and confetti add to this visual tapestry by symbolising the bloodshed and sacrifice of both the beheaded and the freedom fighters, underscoring the revolution’s violent but necessary upheaval. Finally, the single opera singer on the boat signifies the dramatic and far-reaching impact of the revolution as it navigated the course of history to spread democratic ideals and freedom. One could even reason, that the ship symbolises the French Navy and its historic supremacy which played a pivotal role in forming the USA, a nation that was built on the ideas of freedom and democracy much like France. Despite conspiracy theories suggesting a satanic agenda, this powerful portrayal serves as a poignant reminder of the revolution’s critical role in shaping modern society. It encapsulates the very essence of the French Revolution—its fight for liberty, equality, and fraternity—and its enduring influence on the ideals of democracy and social justice around the world.

The Infamous Love Triangle

Immediately following this bloody yet vibrant tapestry, we witness performers draped in colourful outfits swinging on the Pont-des-Arts (known for lovers locking their love for each other with padlocks) on stilts while a video displayed three youths exchanging non-verbal cues through book titles highlighting key French figures, writers and poets and their bold narratives of love, equality and freedom which culminated in them locking themselves in a bedroom leaving suggestible clues of what is to happen next. As expected, similar to the satanic conspiracies of the previous performance, this act also triggered social media unrest of the supposed sexualisation of the games. However, this is just what the visible cues tell us and to in order to go beyond this narrow perspective we recognise that this performance transcends mere sexuality and is more to with freedom, philosophy and the power of literature in French history.

The young love triangle, with its growing attraction and dynamic swings, symbolises the complexity and interconnectedness of human relationships and our inherent need to explore each other and our sexuality – a central theme embedded in French philosophy that later translated its way into literature and cinema. Existentialist thinkers like Jean-Paul Sartre and Simone de Beauvoir explored how love and freedom intertwine, with Sartre’s idea of “bad faith” highlighting the inauthenticity that can plague relationships, and Beauvoir’s notion of reciprocal recognition emphasising the importance of genuine connection. Similar of ideas of how freedom to think is akin to the freedom to love have also being explored in French works of literature and new-wave cinema production that exhibit the profound depths of human emotion and the quest for meaning. Love triangles are a radical symbol that would have been used by thinkers, writers and dramatists to highlight the freedom needed to celebrate love and the inherent indecisiveness that plagues humans during a love triangle. As the performers’ attraction culminates in a cliffhanger, we are left with a heart above the River Seine, beautifully encapsulating the existential belief that love is both a source of profound meaning and a challenge, requiring individuals to navigate the tension between freedom and connection, mirroring the ongoing dialogue within the French intellectual tradition.

Drag Queens & Blue Bacchus in the Last Supper?

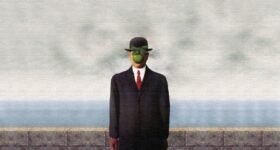

After multiple rounds of performances that delved into French cinema, dance, and music, we were left with perhaps the most provocative one towards the end of the parade of nations. The infamous drag-style recreation of the Last Supper in front of a fashion show concluding with an affluent blue Bacchus dominating the stage. As mentioned, it is up to the viewer to interpret works of art, and as much of the world has chosen, many believe this was an absolute depiction of the Last Supper, leading to instantaneous conclusions of ‘mockery,’ ‘blasphemy,’ and ‘boycotts’ despite representing less than 0.1% of the performances that night. However, if you really know art history, you would realise that the scene depicted was far from the ‘Last Supper’ and was more consistent in depicting Hans Rottenhammer’s ‘Feast of the Gods’. This insight could substantially alter our interpretation, but just for the sake of analysis, If we interpret this performance as the ‘Last Supper’ we reach still reach an ambivalent and unharmful conclusion.

The drag-style recreation of the Last Supper, culminating with the presence of a blue Bacchus, can be seen as a profound critique of human conflict and its inherent futility. I believe by juxtaposing the sacred imagery of the Last Supper-a moment traditionally symbolizing unity, sacrifice, and reconciliation-with the indulgent figure of Bacchus, the performance underscores the senselessness of human strife. The Last Supper, often associated with themes of betrayal and ultimate sacrifice, serves as a poignant reminder of the devastating consequences of discord and the cyclical nature of violence. In contrast, Bacchus, representing excess and hedonism, highlights the distractions and diversions that lead humanity away from meaningful resolution and peace. This striking combination urges the audience to reflect on the wastefulness of conflict and the importance of pacifism. Drag art in this context is implied as a pacifist symbol that resists conflict and war signifying it humble intent to propagate values of peace and unity as opposed to being a shocker or mockery of religion. Even so, it is an artistic metaphor, the power of freedom of expression in France illustrating its rich history in questioning religion, ideology and school of thought through literature, art and fashion which thereby embodies the intrinsic value of art in allowing an artist to explore humanistic themes in a liberated fashion. Although the artwork is inherently provocative and deep, in totality, this entire sequence, delivers us a profound message on the futility of human difference be it on the basis of sex, religion, orientation, class or race being a driver for conflict forcing us to question our proclivity for unnecessary quarrels and indulgences, emphasising that the path to a more peaceful world lies in recognizing and overcoming our differences.

Energetic Youths, Power of Arts & Global Anarchy

From this point on in the ceremony the messages and artistry of performances becomes much more sinister and graver as it reconciles the current injustices of the world whilst questioning their utility and futility in sustaining the human race. While the fashion show persists atop the Passerelle Debilly bridge, another rectangular boat slides in with youths dancing energetically in a contemporary free-style on a canvas that highlights the world and all its injustices from war, poverty and natural disasters culminating in them dropping dead against a red and bloody screen as the entire city goes dark. I deeply appreciate the energy and vibrancy of these youths to continue dancing against the downpour of rain in an endless fashion without an error signifying their relentless determination and resilience much like France’s ambition pull off such a spectacle. Of course, commenters, looked past their appreciation and labelled the sequence as being akin to Zombie apocalypse which maybe true but our analysis does not stop there.

This act single handedly symbolises the power of the arts, be it dance or literature, in confronting and challenging the world’s calamities as it has in France all through its vibrant history. The youths dancing energetically on a canvas depicting global injustices-from war and poverty to natural disasters-reflects the resilience and determination of the human spirit in the face of adversity. Their relentless dance, even under a downpour of rain, signifies their refusal to succumb to these injustices, embodying a powerful stance against the suffering and chaos that plague humanity. It serves as a poignant reminder of the unyielding spirit of resistance and the crucial role of the arts in giving voice to and combating these global challenges. The dramatic culmination, with the dancers dropping dead against a blood-red screen and the city plunging into darkness, starkly illustrates the devastating impact of these issues on all aspects of society and is a commentary of the currents state of the world with issues I very well know you maybe aware of. Despite the grim interpretation by some as a zombie apocalypse, the performance ultimately highlights the arts’ enduring power to inspire resilience, provoke critical reflection, and galvanise collective action against the world’s injustices.

Imagine: A Delicate, Emotional Obituary

As Paris plunged into a still darkness, I was already sensing the eerie presence of war and other social injustices that still perpetuate the world we live in, just in time for it to be rekindled with one of the best performances of the song of the century, “Imagine” by John Lennon. Sung in a poignant and delicate rendition on an island on the Seine by French songwriter Juliette Armanet, accompanied by pianist Sofiane Pamart, whose piano flared in flames, we were presented with one of the most powerful symbolisms of that glimmering sense of hope and optimism amidst a dark and burning world of war, corruption and injustice. “Imagine,” with its timeless call for peace and unity, resonated deeply with the current state of the world, marred by conflict and inequality. It seamlessly connected with the earlier performances by offering a counter-narrative to the despair depicted through the energetic dance against global injustices, the provocative recreation of the Last Supper, and the relentless pursuit of resilience.

This rendition of “Imagine” served as a unifying anthem, echoing the Olympic spirit of bringing nations together in harmony and mutual respect. As the flames of the piano flickered, they symbolised the enduring hope that can emerge even from the darkest times. The song’s vision of a world without borders, possessions, or religions dividing us tied back to the themes of equality and fraternity central to the French Revolution and the existential reflections on love and unity showcased throughout the ceremony. It was a reminder that despite the pervasive darkness, there is always a possibility for light, for coming together to imagine and work towards a better world. This performance encapsulated the essence of the Olympics-a celebration of human potential, unity, and the unwavering hope for a peaceful future, transcending the immediate realities of conflict and strife.

The Saviour Knight

As I felt the glimmer of hope and light in the dark tunnel of the world, France’s metaphorical message continued. A hooded knight on a mechanical horse, bearing the Olympic flag, began its journey along the Seine, destined for the Eiffel Tower where the formalities were to commence. The knight, cloaked in mystery and purpose, was portrayed as a saviour, a beacon of light and optimism in a world fraught with division and strife. As the horse trotted gracefully along the riverbank, its rider became a living embodiment of the Olympic spirit, carrying with it the capacity of sports to reunite the world.

The knight’s journey through the heart of Paris symbolised a bridging of past and present, weaving together the ancient ideals of the Olympics with the modern quest for global harmony. The glowing Olympic flag fluttered in the breeze, representing not just a sports competition, but a universal call to transcend national boundaries, cultural differences and ideological divides. As the knight approached the iconic Eiffel Tower, the vision of Pierre de Coubertin, the father of the modern Olympic Games, played out in a series of historical vignettes and his dream of reviving the Olympic Games in the belief that sport could foster peace and unity among nations, creating a platform for mutual respect and camaraderie. As the knight reached the Eiffel Tower, a symbol of French ingenuity and resilience, this vision was realised as flag-bearing Athletes from diverse backgrounds were shown embracing humanity by carrying their flags in the spirit of sportsmanship under the single Olympic flag carried by the knight reconciling and presenting the intrinsic value of sports in its power to unite the world beyond borders and dispositional differences.

A Perfect End: The Hot Air Balloon Cauldron

Paris 2024 was not all about satanism, mockery and moral corruption as enraged commenters imply. Their opinions, while welcomed, were simply limited by their narrow perspective in seeing past proactive symbols or celebrating the magnificent humanistic messages that were derived from the acts that followed the parade of nations. As I finished watching the ceremony I was dazzlingly captivated by France’s flawless ability rekindle anecdotes of French culture, history and artistic expression with the values of freedom, equality, solidarity and unity whilst transforming the entire city into an ambient and animate stage of visual tapestries.

Inventive, Bold and Humanistic These epithets that I believe define this opening ceremony were finally ignited in the final spectacle of the ceremony. The lighting of the cauldron. As the mysterious X-torch bearer we met throughout the parade hands over the torch back to Zinedine Zidane it was passed through a string of athletes along the river Seine and beyond from Carl Lewis to Rafael Nadal and Tony Parker as they passed through key sites along the 6 km-stretch and relayed through the Louvre. As naive as I was to be still under the impression that the flame would be lit atop the Eiffel tower, I subconsciously knew that the stupefying innovative might would mean this cauldron would not be as simple as that. As one athlete joins the relay after a next, suspense and tension fuelled my psyche until the flame was finally passed onto Olympic champion Charles Coste, the oldest living French athlete at 100 years, who upon gazing at the torch finally offered it to the last torchbearers Teddy Riner and Marie-José Pérec in a way that cyclically reflected the interconnectedness of generations similar to the starting narrative with the catacombs and children.

The flame was beyond inventive in the form of a gigantic hot air ballon that was invented by Joseph and Étienne Montgolfier during the Age of Enlightment in France itself. The beautiful and unique cauldron floated above the city of Paris finally synthetising and reconciling the bold and creative spectacle of a ceremony that France pulled off from the break-free of stadiums, artistic performances and cultural narratives highlighting the true meaning of being human. The cauldron is also symbolic of all-time mankind’s burning ambition to connect with the skies and launch its flight which is synonymous to the competitive spirit of sport equated with France’s ambition to pull off such a ceremony and its timeless historic significance in inculcating the values of freedom, equality and brotherhood. A Perfect end to near perfect ceremony just in time for Celine Dion to captivate the city of Paris as her voice thundered down from the Eiffel tower to the numerous crowds and athletes leaving me and many in tears of joy.

CONCLUSION

Many may label me as biased towards the opening ceremony, but unlike the numerous hate comments that have emerged, I have detailed the logic and rationality behind my appreciation for it. In summary, Paris pulled off a grand spectacle—an inventive and unmatched ceremony on the River Seine that incorporated the entire city through real-time and ambient acts. This ambitious move is worthy of admiration. Furthermore, the focus on the athletes’ experience, exemplified by the boat parade and the act of presenting them to the city, underscores Paris 2024’s hospitable commitment.

Beyond this, the ceremony was a celebration of sport communicated through French culture, artistry, history, and performance, resonating deeply with Olympic values such as freedom, diversity, equality, peace, and unity. The provocative aspects have left some people angry, but much of this hate is fueled by politically correct agendas, media bias, or ethnocentric and illegitimate views of French history and culture. Those with the critical thinking capacity to venture beyond the visible material and extract the inner substance of these performances are more likely to react favorably to the Olympics.

To conclude, we, as humans, especially in the current day and context, are plagued by an inability to think critically and realistically. This leads many of us to reach short-term conclusions that are not thoroughly thought out. This is fuelled by our egocentric attachment to self-ideals and our own thinking framework, causing us to react to and demand that things align with our limited perspectives. This year’s opening ceremony has truly tested the limits of human thinking in the 21st century and is a testament to what the future holds. With that said, Paris 2024’s opening ceremony was a resounding success, and I thank every organizer, artist, and performer behind this masterpiece for their ambition and effort to pull off such an inventive and unique ceremony. While this piece has only looked at the most memorable and provocative moments, there is much more that it has missed, from Lady Gaga’s Cabaret to Celine Dion’s comeback and various other mini-performances that adorned the opening.

This article aimed to inspire readers to think deeper and extract the hidden humanism behind the artistic performances of Paris 2024. By reflecting on the grand spectacle of the River Seine ceremony, the celebration of athletes, and the integration of French culture, I hoped to encourage a more profound appreciation of art and culture. This broader, more inclusive understanding of global expressions invited us to look beyond surface reactions and embrace the deeper meanings embedded in such ambitious and innovative events.

Leave a Comment