Sacred Power and Secular Parallels: How Conclave (2024) Reveals the Political Struggles Within the Church and Society

Sacred Power and Secular Parallels: How Conclave (2024) Reveals the Political Factionalism Within the Church and Society

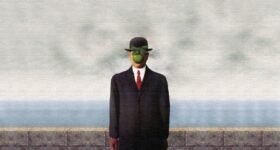

Directed by Edward Berger, Conclave competed for awards against the most critically acclaimed films of 2024, celebrated for its star-studded cast, masterful screenplay, and immaculate production design. Inside the hallowed walls of the Vatican, cardinals from across the globe gather to elect a new pope, but beneath the rituals and prayers simmers a fierce battle of ideology, ambition, and secrecy. The film thus becomes a revelation, exposing how even the most sacred institutions are not immune to the forces of ideological rifts and division. These very forces are set to unfold once more within the Sistine Chapel in the coming weeks, as the election of “God’s Greatest Servant,” as the late Pope Francis once put it, takes shape. In such turbulent times, it is wise to recognise that Conclave’s portrayal of internal power struggles is not just confined to the walls of the Vatican but extends across contemporary society where political polarisation fractures the fabric of our society. It is therefore my objective in this piece to explore four arguments linked to Conclave that mirror the growing polarisation that defines modern society.

The Power of Swing Politics

Informally, swing politics refers to drastic shifts in voter sentiment, where electoral strongholds that once reliably supported a particular ideology or political party drift toward an entirely new one. One of the most commonly observed swings occurs along the broad axis of left and right ideals, while another – often more deeply felt – is the swing between liberal and conservative worldviews. The Liberal-Conservative spectrum is a structural impediment within political rhetoric and electoral discourse that is indisputably part and parcel of the battle to select a new pope. In Conclave, this spectrum is explored through the various political factions that make up the college of cardinals, who through secretive agreements and deals, manipulate the ideological currents that dictate the election of a new pope. These distinct factions predominantly include the Conservative and Liberal factions whose underlying political ideologies serve as the rifts through which electoral sentiments swing across the Conclave.

The Liberal Faction (Led by Cardinal Bellini) – Early in the conclave, Cardinal Bellini emerges as a potential candidate, who backs the support of Cardinal Lawrence and a few other liberal-leaning candidates (The Dean of the College of Cardinals). He symbolises the liberal, reformist faction of the College of Cardinals that pushes for the modernisation of religious scriptures through soft stance on issues such as sexuality, women and race. However, his position weakens significantly after a devastating terrorist attack on the Sistine Chapel. The attack heightens fear among the cardinals, creating a mood where conservative, security-focused ideals gain traction, and Bellini’s softer, reformist agenda begins to seem dangerously naïve to many electors.

The Conservative Faction (Led by Cardinal Tedesco) – The conservatives, led by the Cardinal Tedesco, represent a traditionalist perspective with values and ideals that are more or less congruent to the dominant views that have held Catholic Change for over a millennium. Despite being an early favourite, he astutely capitalises on the climate of fear after the attack, advocating for a strong, unyielding return to Church orthodoxy and authority. However, their momentum falters when Cardinal Vincent Benítez emerges as a moral counterpoint. Benítez’s message of peace, forgiveness, and inclusivity undercuts the fear-driven rhetoric of the traditionalists, offering the conclave a vision of strength through compassion rather than force. This shift reflects how new voices, emphasizing empathy over fear, can unexpectedly realign political landscapes.

This dynamic within Conclave closely mirrors contemporary political landscapes, where crises – whether acts of terror, economic collapses, or pandemics – often trigger a sharp swing towards conservative, security-driven politics. Similarly, periods of stability or instability under a conservative leaderships tends to favour progressive movements advocating for reform and inclusion. The film captures how ideological swings are less about coherent visions for the future and more reactive to fear, uncertainty, and the human desire for stability. In today’s society, we witness the same phenomena: moments of crisis fortify traditionalist forces, while emerging voices championing empathy and global solidarity struggle to find footing, only to eventually reshape the political conversation when the appetite for fear wanes. While exogeneous, like an act of terrorism, in the film could easily catalyse and expedite such a swing in ideology, the underlying force that powers swing politics is not exogenous nor endogenous shocks. Ultimately, it is a powerful group of undecided centrists that dictate ideological shifts whose uncertainty is what drives the forces of society as it did in Conclave.

Political Centrism as a Parameter of Uncertainty

In political theory, centrism advocates for gradual change through a diplomatic stance that resists both the right’s adherence to the status quo and the left’s pursuit of radical transformation. Unlike the liberal and conservative factions, which are hallmarked by clear leaders and ideological markers, the centrist faction within Conclave remains elusive, lacking both defined leadership and explicit values in the papal context. Although the film intentionally refrains from spotlighting any figures as explicitly centrist, it is indisputable that they collectively form the greatest majority within the College of Cardinals. This is evidenced by the repeated ideological shifts across each ballot and the ultimate twist that sees Cardinal Benítez secure the papacy. These fluid shifts mirror the cognitive and emotional volatility often seen among centrist voters, suggesting that centrism in the Vatican is less a coherent ideology than a void. Paradoxically, it is this very lack of ideological rigidity that propels the Conclave towards consensus, with the majority’s uncertainty ultimately determining the course of the Church’s future.

In this way, political centrism, with no definite definition, serves as a parameter of uncertainty – a force that can either stabilise or paralyse institutional decision-making depending on the pressures at play. Applied to broader society, centrism offers the virtue of moderation: the ability to cool down extremism, seek compromise and adapt to complex realities without resorting to ideological purism. However, its vice lies in its inherent ambiguity; in moments of profound moral or political crisis, the centrist impulse toward caution can devolve into indecision, allowing more extreme forces to set the terms of debate. In Conclave, as in the real world, the centrists’ reluctance to commit to bold positions prolongs instability, but ultimately their quiet, collective shift determines the course of history – illustrating how the “middle ground” often holds more power than either side realises, for better or for worse.

The Curse of The Populism

Beyond the liberal, conservative and centrists faction, is another faction that we are indirectly exposed to in the form of populism. In political rhetoric, populism is political philosophy that strives to appeal to ordinary people when their needs are disregarded by dominant and elite groups within society. It is an aspect of politics we witness daily as politicians carefully craft their image to represent the needs of the common man promising policies that work towards the utilitarian good of broader society. In Conclave the populist faction is primarily led by Cardinal Tremblay who positions himself as a man of the people, using simple slogans and emotional appeals rather than complex theological arguments to gain support. Yet, as the conclave progresses, his opportunism becomes apparent, and his shallow rhetoric is exposed through an event that represents the cursed hypocrisy of populism as the next paragraph illustrates.

Working with Sister Agnes, the head housekeeper, Cardinal Lawrence discovers that Cardinal Tremblay arranged for the sudden transfer of a servant to create issues with anotehr candiate and conceal evidence of the electoral corruption he had taken part in. Breaking into the late pope’s sealed apartments, Cardinal Lawrence uncovers documents revealing that Tremblay had bribed cardinals to secure his votes, a revelation that shakes the integrity of the conclave. . This sequence embodies The unwritten Curse of Populism: Tremblay, who rose on promises of humility and service to the people and College of Cardinals, is unmasked as a self-serving opportunist, demonstrating how populist rhetoric often cloaks corruption and ambition, ultimately deepening public distrust in institutions that claim to represent moral authority. It is a trap that ordinary citizen could easily fall to as they are swayed by politicians choosing to represent their interests by antagonising the existence of elites through an image that hides their corrupt ambitions.

Does Political Pragmatism win at the end of the day?

Ultimately, all factions — liberal, conservative, centrist, and populist — fail to secure the papacy due to their inability to unify the College of Cardinals and form a majority. It is Cardinal Benítez’s nuanced response to the terrorist attack that allows him to transcend these fractured ideologies and emerge as the true figure of political pragmatism. While the liberal faction falters with its idealistic calls for reform and the conservatives cling to fear-driven orthodoxy, Benítez’s approach stands out by focusing on reconciliation, peace, and unity. His pacifist stance not only addresses the immediate crisis but also offers a broader, more inclusive vision for the Church’s future, healing divisions and bridging gaps between the conflicting factions. By recognizing that the true challenge lies in overcoming fear and division, rather than perpetuating it, Benítez successfully shifts the ideological battleground away from rigid politics to a more humanitarian and pragmatic vision. His election illustrates that, in times of great crisis, political pragmatism — the ability to adapt, heal, and unify — proves to be the most effective and enduring ideology.